By John Mihaljevic

In this essay I argue that the hyperscalers, by ramping up AI-related capital spending to unprecedented levels, have set themselves on a perilous path, away from high-margin, capital-light models toward a capital-intensive future in which their return-on-capital and margin profiles are highly uncertain.

This AI-driven capex frenzy is eerily similar to the telecom bubble of the late 1990s and early 2000s. Extravagant spending on fiber optics and network infrastructure promised growth but delivered catastrophic oversupply and collapsing prices. Today’s hyperscalers may be repeating history’s costly mistakes.

Capital cycle theory suggests that this massive investment wave, rather than securing dominance, could become a value-destructive exercise. With hundreds of billions flooding into AI infrastructure, competition is poised to intensify rather than diminish. High costs threaten to compress margins, as driving high utilization of fixed-cost infrastructure becomes a priority.

While free cash flows are already contracting, investors still view the spending generously as “growth capex” in the service of future market dominance. Such willingness may wane if a more sobering picture of the competitive landscape and prospective returns on capital begins to emerge.

Ironically, the ultimate winners of the AI arms race may not be the hyperscalers themselves, but nimble, asset-light companies riding atop their infrastructure—much like Netflix capitalized on telecom and cable’s broadband investments. These smaller, specialized firms could capture disproportionate value by creating innovative AI services without incurring the heavy capital burden plaguing the larger players.

Finally, the less glamorous, asset-heavy sectors providing critical commodities and industrial products—for power generation, electrical wiring, cooling, and more—stand to reap substantial benefits from the hyperscalers’ capital deployment. Yet, sector leaders remain available at below-market multiples.

Investors should consider the risk-reward: as the hyperscalers aggressively wager their enviable business models on an uncertain future, a “new generation” of more agile players and an “old generation” of commodity-based businesses may end up capturing a lion’s share of the economic value created.

The Great AI Capex Surge

Not since the dot-com buildout of the late 1990s have we seen capital spending on tech infrastructure at the scale now unfolding. Over the last two years, the largest tech companies have dramatically loosened their purse strings to fund an AI computing arms race. Data centers packed with AI chips don’t come cheap, and the numbers are staggering.

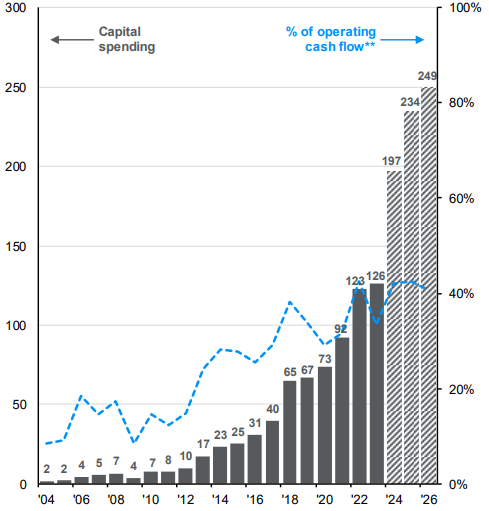

In 2024 alone, the five biggest hyperscalers poured an estimated $197 billion into AI-related infrastructure. That marks an inflection from prior years, up more than 50% from roughly $126 billion in 2023. And the trajectory points steeply upward: J.P. Morgan Asset Management projects these companies’ combined capital outlays will reach $234 billion in 2025 and $249 billion in 2026. The hyperscalers are now investing in one year what they used to spend over a decade not long ago.

Capex by AI Hyperscalers: Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, Oracle ($ billions)

Source: J.P. Morgan Asset Management.

Training large language models and running AI services at scale require vast computing and storage. A few notables from recent disclosures:

- Amazon plans to spend $100+ billion on capital projects in 2025, up from about $75 billion in 2024 and roughly $50 billion in 2023. Andy Jassy defends the splurge as seizing a “once-in-a-lifetime” opportunity.

- Microsoft is projected to spend about $80 billion on AI data center infrastructure (excluding its OpenAI partnership) in 2025, roughly double its recent capex. Management has indicated a multi-year investment cycle to build out Azure’s AI computing capacity. According to Satya Nadella, Microsoft is “all-in” on AI.

- Alphabet reportedly plans around $75 billion in capex for 2025 , above analysts’ prior expectations of ~$58 billion. Sundar Pichai defends the spending as critical to “build infrastructure for future applications.” However, Google’s high-profile AI products have yet to prove they can monetize at scale.

- Meta’s capex is projected at $60–65 billion in 2025, an increase from roughly $40 billion in 2024. At $60+ billion, Meta’s capex would be roughly one-third of its 2024 revenue, suggesting how capital-intensive the business is becoming.

- Oracle has also jumped on the AI infrastructure bandwagon, partnering with NVIDIA and others to offer cloud GPU capacity. Heavy capex in 2025 and beyond follows capex in the high single-digit billions in 2024.

- SoftBank has emerged as a wild card. In January, OpenAI, SoftBank, and Oracle a new joint venture dubbed “Project Stargate,” aiming to invest up to $500 billion over four years to build AI data centers across the U.S. The initial phase is $100 billion, with SoftBank and OpenAI each committing $19 billion as lead partners. Speaking at an event in late 2024, Masayoshi Son envisioned an artificial superintelligence by 2035 that would require “400 GW of data center power” and 200 million AI chips — at a cumulative capex cost of $9 trillion. Yes, trillion with a “t”. He argued that $9 trillion could be “very reasonable” and even remarked that $9 trillion might be “too small” an investment in the grand scheme. Such statements reflect a mindset that no sum is too great in pursuit of AI dominance.

- Apple, Alibaba, Tencent, and other major players are not even considered here, but they will undoubtedly play a role in — and add to — the massive spending.

Taken together, the hyperscalers’ AI capex binge is without precedent. By 2025, just four companies are on track to spend over $320 billion combined on capex. That’s larger than the GDP of countries like Chile or Finland. It also represents a large portion of these firms’ revenues — on average over 20% of sales in 2025, roughly double the percentage from a decade ago.

Big Tech is quickly moving from asset-light to asset-heavy. AI is seen as vital to remain competitive, and not investing aggressively could mean ceding ground to rivals or upstarts. The hard questions: What is the timeline for payback? How much of this spend is truly “growth capex” that will generate high returns, versus just keeping up with the Joneses? The history of tech and infrastructure booms is littered with examples of overinvestment.

Asset-Light to Capital-Heavy

For years, the hyperscalers were paragons of the asset-light, high-margin business model. They demonstrated how scaling software and networks could generate enormous revenues with relatively limited physical assets.

The “AI infrastructure” business is fundamentally more capital-intensive than the pure software or advertising businesses that drove past growth. As hyperscalers invest tens or even hundreds of billions in steel and silicon, they start to exhibit traits of heavy industries or utilities.

The most immediate effect of the AI build-out is the pressure on free cash flow. The hyperscalers are still growing revenue healthily, but capex is growing much faster. According to Morgan Stanley, the hyperscalers’ combined FCF actually fell year-over-year in the second half of 2024, and they project FCF to drop 15–20% in 2025 despite revenue growth. Analysts across the board have been revising down FCF forecasts for 2024–26 by on the order of 20+% to reflect the higher spend.

Meta in 2024 generated a record ~$52 billion in FCF. However, with capex set to jump from ~$40 billion in 2024 to potentially $60+ billion in 2025, even if Meta’s operating cash flow grows, FCF could be nearly halved. Similarly, Amazon’s FCF, which was already thin relative to earnings because of heavy fulfillment and AWS investments, could be consumed entirely by AI-related capex.

The income statement will reflect this over time through higher depreciation. Cloud providers already depreciate servers over short lifespans. As capex front-loads costs on the balance sheet, operating margins will feel the drag of accelerated depreciation. Of course, company managements and sell-side analysts will then steer investor attention away from reported earnings toward cash earnings, just as they currently suggest investors look at cash earnings but exclude growth capex. And throughout, investors should pay scant attention to stock-based compensation.

Financial reporting gymnastics aside, the financial profile of hyperscalers may start looking less like the high-flying 2010s and more like that of mature, capital-intensive businesses where cash flows are reinvested as fast as they come in. This could lead to a pivotal change in the investment narrative, especially if we enter a period of greater market volatility and lower investor tolerance for pie-in-the-sky thinking.

From “Scalable” to “Saturated”?

The market historically afforded hyperscalers premium valuation multiples because of their scalable models and wide moats. A critical question: does the move to capital intensiveness undermine those moats?

Morgan Stanley highlights that hundreds of billions have been — or are about to be — plowed into AI by hyperscalers and VCs, yet recent developments like open-source AI models challenge the idea that only a few big firms will reap the rewards. DeepSeek reportedly achieved GPT-4 level performance with far fewer parameters and less hardware, calling into question how much data center muscle will ultimately be needed for advanced AI. If AI innovation allows more to be done with less, the hyperscalers may find they overspent on capacity that isn’t utilized at pricing levels assumed. In such scenarios, the competitive advantage one hoped to secure by massive spend dissipates — a classic capital cycle pitfall.

If investors come to view these companies as quasi-utilities or heavy industry players, we could see a de-rating. For instance, utility companies or telecoms with large asset bases but moderate growth often trade at single-digit to low-teens P/E ratios. At the peak of the 2000 tech bubble, telecom equipment makers like Cisco were valued like high-growth stars; a few years later, they traded more like cyclical industrials.

Another aspect is capital returns. Asset-light tech companies generate copious excess cash, much of which has been returned via buybacks. But if cash is tied up in capex, fewer buybacks occur, potentially reducing EPS growth.

Big Tech may effectively “nationalize” a chunk of its business model — pouring shareholder money into infrastructure in a way akin to state utilities, but without state-like guaranteed returns.

The Telecom Boom and Bust

“Build it and they will come.” That was the mantra of telecom entrepreneurs in the late 1990s, much as today’s tech giants seem to believe “build it and AI will come.” The telecom frenzy, which saw companies lay tens of millions of miles of fiber optic cable and construct vast networks, holds lessons for the AI infrastructure race. Back then, as now, the lure was exponential demand and the fear of missing out on a paradigm shift. And back then, as may happen now, reality fell far short of hype, leaving a glut of capacity, crushed prices, and investor carnage.

To be clear, I am a firm believer in the utility and strong growth of AI. The challenge as an investor is to figure out where my capital will be treated best. It is quite easy to get blinded by the promise of returns. Examples abound: automobiles (revolutionary as compared to horse-drawn carriages), airlines (revolutionary as compared to other forms of long-distance travel), mobile phone service (revolutionary as compared to old-school telephony), and other hugely beneficial innovations.

Following the U.S. Telecom Act of 1996, dozens of carriers and network builders sprang up. Incumbents and startups raced to install fiber-optic networks, convinced that an explosive growth in internet usage would require vastly more bandwidth. Companies like Level 3, Qwest, Global Crossing, 360networks, Williams, and WorldCom raised and spent hundreds of billions of dollars in aggregate. WorldCom’s CEO claimed in 1996-97 that Internet traffic was doubling every 100 days — an exaggeration — but it fueled a frenzy of investment as firms feared falling behind.

Global Crossing — Stock Price, 1998-2002

A poster child was Global Crossing, founded in 1997 with a bold plan to lay undersea fiber linking continents. In just eighteen months, Global Crossing went public and saw its valuation skyrocket to $47 billion by 1999. It epitomized the era’s hubris. By 2001, the tides turned. Demand did grow, but not nearly to the level the capacity builders expected. By late 2001, Global Crossing was hemorrhaging cash — it lost $3.4 billion in Q4 2001 on $793 million of revenue. The overbuild was so severe that much of its fiber lay dark. In early 2002, Global Crossing filed for bankruptcy — one of the largest bankruptcies at the time, wiping out equity holders.

The entire sector imploded. By the mid-2000s, around 85% of the fiber optic cable laid in the late 90s remained unused. Companies had installed far more capacity than the market needed. Even four years after the dot-com bust, the vast majority of strands were unlit. Bandwidth prices plummeted ~90% in the early 2000s. This is basic economics: when supply overwhelms demand, prices crash. The value of network capacity fell to a fraction of what companies had projected, ruining their business cases. Contracts that were expected to yield rich returns became nearly worthless.

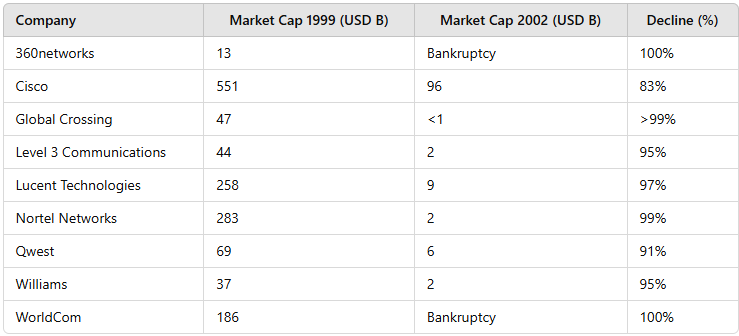

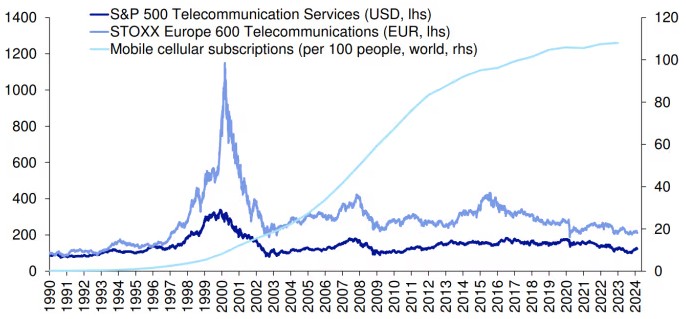

A “trillion-dollar telecom boom” turned into a trillion-dollar bust. From the market peak, about $2 trillion of market cap was erased in telecom stocks, contributing heavily to the broader market downturn. That $2 trillion figure would correspond to a much larger figure in today’s market.

Telecom Boom Darlings — Before and After

Sources: SEC filings, historical market data, and company reports.

Two dozen telecom companies went bankrupt in 2001-2002 alone. WorldCom, led by Bernie Ebbers, had grown via acquisitions and network builds, only to be felled by both accounting fraud and a wildly overbuilt network carrying price-depressed traffic. The industry accumulated over $1 trillion in debt by 2002, much of which had to be written off. As FCC Chairman Michael Powell noted then, a huge portion of the debt incurred to fund these networks would “never be repaid”.

The Price of Overspending: Telecom Stock Performance vs. Mobile Adoption

This was a classic case of overestimation of demand and underestimation of competition, leading to gross capital misallocation. Each player assumed if they built a superior network, they’d capture the lion’s share of surging internet traffic. But everyone assumed that, so everyone built, leading to massive oversupply. In capital cycle terms, high anticipated returns attracted too much capital, which destroyed those very returns.

The parallels to today’s AI infrastructure race are striking — and a bit eerie:

- Exponential demand forecasts: Then it was internet traffic; now it’s AI model demand. In the 90s, many genuinely believed every home would soon need massive bandwidth, and that businesses would require unlimited data — true in the long run, but the timing was off by a decade or more. Could AI demand likewise take longer to materialize than the rosy projections suggest?

- Cheap capital facilitating overbuild: The late 90s featured easy capital — IPOs, bond offerings, and loans were plentiful for any company with a fiber story. This led to less discipline in investment decisions — exactly what capital cycle theory warns. SoftBank’s ability to marshal $100 billion for “Stargate” and the hyperscalers’ war chests are analogous to the glut of funding telcos had in 1999.

- New entrants and competition: In telecom, deregulation opened the field to many new competitors. In AI cloud, while the hyperscalers are few, we do see others — e.g., Oracle partnering with NVIDIA, startups like Cerebras building specialized AI supercomputers, not to mention China’s tech giants. We might witness a price war in AI cloud services reminiscent of bandwidth price collapses. Already, some cloud providers are differentiating on price per GPU-hour or offering discounts to lock in AI customers.

- Speculative excess and reality check: Telecom’s motto was “if we build the network, uses for it will come.” Killer applications did ultimately arrive, but not fast enough to save the over-investors. One warning sign: Goldman Sachs points out that while Big Tech has ramped capex to fuel generative AI, they “have yet to show sustainable business models” for these investments.

- Hubris and overconfidence: The late-90s telco executives were brimming with confidence — they were building the future’s highways, and nothing seemed too expensive or too large-scale. Mark Zuckerberg declaring a “year of efficiency” in early 2023 has quickly shifted to effectively a year of inefficiency as he doubled capex for AI. That cognitive dissonance — needing to invest heavily to not be left behind, even if it hurts financial efficiency — is reminiscent of prior attitudes.

The survivors of the telecom bust did lay a foundation for future growth. The fact that 85% of fiber was dark in 2005 meant that companies like Netflix and Google in 2010 could stream video because bandwidth was abundant and dirt cheap. The infrastructure did get used — just under new ownership at pennies on the dollar. Infrastructure investments often pave the way for someone else to profit.

From 2000-2002, telecom stocks lost on average ~80-90% of their value — a wipeout rarely seen outside depressions. I do not anticipate a similar cataclysm for Big Tech, but even a partial parallel is worrisome and not reflected in the consensus.

Infrastructure vs. Over-the-Top: Who Captures the Value?

A pattern repeated throughout modern economic history is that those who provide fundamental infrastructure often struggle to capture as much value as those who build services on top of that infrastructure. Railroads vs. those who shipped goods on them, telegraph wires vs. financiers arbitraging information, telephone networks vs. call services — the list goes on.

In the 2000s, the term “over-the-top” arose to describe services that ride on telecom/cable networks without owning them. The OTT providers have often created disproportionate shareholder value relative to the infrastructure providers. I see a potential analog in the AI landscape: the hyperscalers are building the “rails” and “pipes” of AI, but the biggest value creation might come from clever, asset-light companies that use those rails to deliver AI-driven products and services.

Netflix vs. the Cable/Fiber Companies

In the late 90s and 2000s, telecom and cable firms invested massively in broadband networks. By mid-2010s, high-speed internet had become ubiquitous in developed markets, thanks largely to those investments. However, the investors in many of those networks had meager returns. Telecom companies like Verizon, AT&T, Comcast, and their global peers often traded at low multiples, burdened by debt and heavy ongoing capex for maintenance and upgrades.

Netflix, founded in 1997, pivoted to streaming video around 2007. The company did not build any broadband network; it simply leveraged the internet connections its customers already had. By investing in content and a user-friendly platform, Netflix rode on top of the cable/fiber infrastructure. Netflix is now worth more than any individual telecom or cable company. The OTT player captured the value while the network owners were often relegated to lower-margin “dumb pipe” roles.

European telecom CEOs argued that companies like Netflix, YouTube, and Facebook were “free-riding” on their networks — using bandwidth that cost billions to deploy, without paying network operators beyond basic transit fees. Calls for “fair share” payments emerged. But regulators largely didn’t force OTTs to pay extra; instead, telcos had to be content with selling bandwidth as a commodity. The investment risk was borne by the network builders; the rewards reaped by application builders.

YouTube became a massive video platform without Google laying a single cable to homes — it relied on broadband networks built by others. WhatsApp and Skype essentially displaced a huge portion of telcos’ high-margin SMS and international call revenue by using the internet as a free transmission medium. The telcos provided the connectivity, but third parties claimed the profit pools.

The pattern extends beyond telecom. In computing, the “Wintel” era saw Microsoft and Intel capture most of the profits of the PC revolution, not the manufacturers of hard drives or memory chips. In cloud computing, ironically, Amazon AWS was initially an OTT service riding on data centers and connectivity provided by others — though Amazon quickly vertically integrated by building its own data centers.

AWS Capex vs. AI Infrastructure Capex

Some may argue the example of AWS serves as proof that a high-capex business can create massive value. However, Amazon’s capital spending on AWS fundamentally differs from its and other hyperscalers’ massive investments in AI infrastructure.

AWS had an inherently clearer and lower-risk business case from inception because Amazon itself was a guaranteed customer. AWS was launched as a capital-light experiment leveraging Amazon’s existing retail infrastructure. Early capex was modest, amounting to tens of millions per quarter, and Amazon gradually expanded AWS only as real customer demand materialized. By the time AWS publicly launched services like S3 in 2006, thousands of developers were already signed up, providing immediate revenue and justifying further investments.

In sharp contrast, today’s AI infrastructure involves enormous upfront capital commitments. Collectively, Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and Meta are projected to spend over $300 billion in a single year on AI infrastructure. This level of investment vastly surpasses AWS’s gradual, demand-driven approach, representing a speculative build-out based largely on anticipated rather than proven revenue streams.

Moreover, AWS scaled in a relatively benign competitive environment. In its early days, AWS had limited competition, achieving substantial market share before rivals like Microsoft Azure and Google Cloud gained traction. This allowed AWS to build a dominant position and maintain pricing power. The AI infrastructure market is intensely competitive and global from the outset.

Asset-Light Innovators in the AI Era

Who could be the “Netflix of AI” — the agile, capital-light companies that leverage the hyperscalers’ AI infrastructure to deliver high-value solutions?

A few possibilities:

- AI-powered software startups, which do not train their own giant models from scratch; instead, they use APIs from OpenAI, Azure, AWS, or fine-tune open-source models on rented cloud infrastructure. They pay usage fees; the multiple on those costs could be high if they deliver unique value to end-users.

- OpenAI itself began as an asset-light layer on top of Microsoft’s Azure. When ChatGPT took off in 2023, it was running on Microsoft’s data centers. OpenAI’s value skyrocketed, despite OpenAI not owning the vast majority of the hardware. It has since involved more complicated partnerships.

- Consumer AI apps and platforms may scale to hundreds of millions of users without owning hardware. Think of an AI-driven social network, or a personal AI assistant app that becomes ubiquitous.

- Integration and consulting offer another asset-light opportunity. Companies that become experts at weaving AI services into business workflows could add lots of value. Their main assets are human capital and perhaps some proprietary data.

- Open-source ecosystem: Hugging Face, a platform for sharing AI models, has become a critical hub for AI developers. By facilitating model distribution and community building, Hugging Face’s value lies in its network, not hardware.

In essence, the OTT opportunity is any business that leverages the plentiful AI computing power being built, without sinking capital into it, to deliver something uniquely useful or creative. I would not be surprised if some of the most valuable AI companies end up having relatively low fixed-asset bases. They might monetize data, algorithms, or networks of users rather than compute infrastructure.

Software Incumbents: More to Lose Than to Gain?

Software-as-a-Service giants like Salesforce, Adobe, ServiceNow, and SAP have enjoyed high growth, robust pricing power, and premium valuations, benefiting from hyperscaler infrastructure. However, the AI boom poses serious risks to their dominance. AI represents more than a new feature; it’s a paradigm shift capable of fundamentally altering how software is consumed.

AI lowers barriers to entry, enabling startups to rapidly develop powerful, AI-driven software at reduced costs. The result is an influx of competitors targeting every niche within SaaS. Hundreds of AI-powered alternatives emerge weekly, flooding markets previously dominated by large incumbents. This surge erodes incumbents’ pricing power, as businesses gain leverage to negotiate lower prices or switch providers.

AI may also commoditize SaaS platforms through AI-powered agents. As they mature, autonomous agents will likely become the primary user interface, relegating SaaS platforms to backend utilities. This shift drastically reduces the value of distinct SaaS brands, user interfaces, and specialized features.

History illustrates how rapidly incumbents can collapse when competition surges dramatically. Groupon, for instance, initially enjoyed explosive growth, yet quickly faced thousands of copycat competitors due to easily replicable technology and low barriers to entry. This intense competition swiftly undermined Groupon’s uniqueness and profitability, causing severe erosion in market share and valuation.

Satya Nadella underscored this existential risk to SaaS in a recent interview by asserting, “the notion that business applications exist, that’s probably where they’ll all collapse in the agent era.” Nadella sees AI agents supplanting SaaS workflows, shifting critical business logic into a dynamic AI layer. He foresees value shifting from standalone SaaS platforms to integrated AI-driven interfaces and automation layers, fundamentally altering the competitive landscape.

See the first four-and-a-half minutes:

Will Hyperscalers Move Up the Stack?

The hyperscalers are trying to play on both levels — providing infrastructure and building AI services. In a sense, they are attempting to be both the railroad and the train, to capture value at multiple layers.

This is wise strategically, but it’s challenging culturally. Focus is a finite resource. The likes of Netflix succeeded because the telcos weren’t great at creating streaming services. Similarly, startups may always have the agility and domain-specific focus to out-innovate a generalized platform on particular use cases.

Capital Cycle Theory: Will Hyperscalers’ AI Investments Destroy Value?

Applying the theory laid out in the seminal book Capital Returns to the hyperscaler AI frenzy yields some sobering conclusions. Over the past decade, Big Tech enjoyed extraordinary profits, which signaled an open invitation: “invest here, the returns are great.” And invest they did — initially in areas like new ventures and R&D — but by 2022-2023, a clear target emerged: Generative AI.

“High profitability loosens capital discipline,” as Marathon Asset Management’s capital cycle framework states — companies with flush profits are inclined to boost capital spending. That’s exactly what happened: cloud profits were reinvested into yet more capacity. And just as the theory predicts, competitors are following suit — no one wants to be left behind, and no CEO wants to tell the Board “we missed the AI boat”. CEO egos and tech FOMO reinforce the cycle: even if internally there are doubts, externally everyone exudes confidence and doubles down.

One marker of potential overinvestment is when capacity growth outpaces demand growth. Are we seeing that? Early signs suggest maybe. By late 2024 cloud GPU shortages seemed to be easing. If all hyperscalers have significantly more GPU clusters by 2025, they will be eager to rent them out — possibly pushing each other on price or sales incentives to win customers. We also see a proliferation of AI chips, which could flood the market with compute options. Capital cycle theory warns that the competitive position of firms deteriorates when everyone has expanded supply.

If indeed this is an overbuild, we will see the next phase as returns on capital decline. Already, hyperscalers’ FCF-to-revenue and ROIC are trending down. The crucial question is whether future profits will rise enough to justify the capex. Capital cycle analysis is inherently skeptical of such happy endings when a lot of capital is chasing a theme. It posits that unless there is some barrier to entry or restraint, the increase in supply will outstrip what demand can profitably absorb. A few scenarios:

- AI compute becomes a commodity service, with thinning margins.

- Some fraction of this expensive capacity sits idle, or is utilized but at such low pricing that ROI is subpar. For example, if open-source efficient models reduce the need for massive GPU hours, customers might use smaller clusters or edge devices to do tasks, stranding some hyperscaler capacity.

- The extreme outcome: Write-downs or restructuring — recall how Intel had to write off manufacturing capacity in past downturns. In cloud, a direct writedown would be unusual since servers can be repurposed, but we might see a slowdown and layoffs in the data center construction, or cancelled projects.

The capital cycle perspective argues that the presence of well-capitalized competitors investing simultaneously virtually assures that capital will be misallocated. Marathon’s approach would have investors look for the opposite: industries where capacity is leaving or consolidating, not entering. Right now, AI infrastructure is clearly in an expansion phase, not consolidation.

Let’s consider barriers and mitigating factors:

- Is there an oligopoly that can rationalize capacity? In some industries, a few players coordinate to avoid glut — think OPEC in oil, or semiconductor foundries scaling more carefully. In cloud AI, while it’s effectively an oligopoly of three to five in each region, they are in hyper competition, not cooperation.

- Technological leapfrogs: A risk of heavy investment is tech obsolescence. Companies might be stuck with last-gen infrastructure if a new breakthrough emerges. If someone figures out an AI algorithm that is far more efficient, suddenly you don’t need as many GPUs or large clusters. DeepSeek’s R1 model is an open-source model that purportedly challenges closed models with less compute. If such approaches proliferate, the scale of compute might become less of an advantage. In capital cycle terms, that would mean the assumption that more capital = more moat fails; instead it becomes sunk cost with no moat.

- Regulation or external shock: A non-economic factor could also derail returns. Suppose regulators in the EU or US impose restrictions on AI deployment or require expensive compliance that reduces profitability. Or perhaps an AI safety issue leads companies to pause certain projects.

The capital cycle may turn as follows: Companies start showing poor returns, stock prices lag, investors get frustrated. Eventually, management teams may pull back on capex. Some weaker players might exit or scale down. Consolidation or sharing could occur — maybe companies collaborate on AI infrastructure to avoid redundancy. As capital investment slows, the oversupply gradually clears with growing demand, and the survivors eventually see better returns again.

We’re not at the bust phase yet — we’re arguably at the peak of enthusiasm heading toward the crest of overcapacity. But investors should be watching for signs of peaking. For example, management rhetoric. Earlier in 2023, tech CEOs were extremely bullish on AI. By early 2025, some tones are shifting to temperance, emphasizing efficiency of models.

A key concept from Capital Returns is that it often pays to invest against the capital cycle. That might mean, for instance, looking at other sectors now unloved because so much capital is going to AI — those other areas could face less competition and yield better returns. Or even within tech, maybe the second-order beneficiaries might be better investments than the hyperscalers during this heavy-build phase.

In AI, the combination of herd behavior, hubris, and cheap capital from prior success is textbook. The trillion-dollar question: will this cycle break the way of telecom or can Big Tech manage a softer landing? Big Tech has much more diversification and financial resilience than the one-trick telecom ponies did. Even if AI capex overshoots, these firms have other profit streams to cushion the blow. That might prevent outright disaster, but it could weigh on valuations.

Feeding the AI Beast: Asset-Heavy Beneficiaries of AI Growth

Asset-heavy, commodity-based businesses meeting AI’s needs are companies that provide the raw inputs and physical necessities for AI data centers — from electricity to cooling systems to critical materials like copper. As AI infrastructure demand soars, these suppliers could experience a secular boost in volume and pricing power.

Electricity

Deloitte estimates data centers will account for 2% of global electricity consumption in 2025 and could double to ~1,065 TWh by 2030 — more electricity than some G20 countries consume annually — largely driven by power-intensive AI growth. If I was a betting man, I would take the over on Deloitte’s 2030 estimate — by a lot.

Electricity is the oxygen of AI, and those selling it will see increased demand. If supply struggles to keep up, electricity prices could rise, benefiting generators’ margins. AI data centers could strain grids, which could be good for power producers’ businesses if managed well.

For electric utilities, particularly in regions with major data center clusters, AI is a source of major demand growth. Utilities that can supply this power reliably stand to benefit from high load factors and long-term purchase agreements with data center operators. Moreover, AI centers often require 24/7 stable power with redundancy. This can translate into investments in not just generation but also grid infrastructure.

One nuance: hyperscalers also invest in renewables and sometimes become their own power providers. But they still typically pay utilities or independent power producers. The regions that become AI hubs might see their local utilities’ revenues surge. For example, in Quincy, Washington or parts of Utah and Oregon, large cloud data centers have become the dominant customers for local power companies.

There’s even talk of innovative solutions like small modular reactors dedicated to powering data centers. If that happens, companies in nuclear tech or other generation tech could find a new customer base in hyperscalers.

Cooling and HVAC

Running tens of thousands of high-performance chips in close quarters produces enormous heat. Traditional air cooling is hitting limits in AI data centers. Advanced cooling solutions are in high demand — from chilled water systems to immersion cooling where servers are dunked in special fluids.

Cooling is not trivial: cooling systems can consume up to 40% of a data center’s electricity themselves. So improving cooling efficiency directly lowers operating costs. Companies that provide industrial chillers, heat exchangers, liquid cooling equipment, fans, and air handlers are seeing a boom. For instance, Vertiv, a company specializing in data center power and cooling, has reported strong orders tied to data center expansion. Others include Schneider Electric, Siemens, Johnson Controls, and niche firms like Rittal or Daikin that have data-center-specific cooling products.

Liquid cooling is gaining traction because it can handle high-density racks better than air. It can also reduce or eliminate the need for chillers in some designs. Companies innovating in this space could become key suppliers. Even large chip makers like Intel have initiatives on new cooling approaches.

Water suppliers also indirectly benefit — many data centers use evaporative cooling which consumes water. As noted, a 30MW data center can use >50 million gallons of water a year for cooling. That has started to raise sustainability concerns, but it’s an opportunity for water treatment and supply companies, or for firms offering waterless cooling tech. Horizon’s Murray Stahl has made the case for an investment idea that may benefit from rising demand for water cooling — San Juan Basin Royalty Trust.

Beyond GPUs: Semiconductor and Hardware Beneficiaries

Leaving aside the obvious — and highly valued — beneficiaries of AI chip demand, it’s clear that AI data centers need power equipment, electrical components, and networking gear. Even seemingly mundane things like server racks, power distribution units, and backup generators are in higher demand. For example, Cummins and Generac produce backup generators for data centers to ensure uptime during grid outages.

Memory manufacturers also benefit: AI workloads are memory-intensive, driving demand for high-end DRAM and SSD storage. They are asset-heavy and have been ramping production of specialized high-bandwidth memory for AI GPUs.

Building data centers requires a lot of construction work and often land in specific areas. Data center REITs own data centers and lease to tenants — though hyperscalers often build their own, some still lease colocation space for certain needs. If the hyperscalers ever slow building in-house, they might rent more, which could help these REITs. Construction firms that specialize in tech infrastructure have robust business building out these facilities.

Copper and Raw Materials

AI data centers use vast amounts of copper in power cabling, connectivity, and even within chip interconnects. Copper is critical for electrical conductivity in these high-power environments. An estimate from Man Institute notes that US data center expansion for AI could add 0.5-1.5% to global copper demand. Again, I would take the over on that, by quite a lot. The copper market is often in tight balance, so even a low single-digit swing can mean the difference between surplus and deficit. A sustained low single-digit increase in demand without commensurate new supply could create a copper shortage and drive up prices.

Copper miners and producers could indirectly ride the AI wave. Copper prices have already been buoyed by the clean energy transition; AI data centers add another source of secular demand.

Similarly, other materials: rare earth elements, specialty plastics and composites, and silicon photonics components. While these commodity suppliers are asset-heavy and often low-margin, a demand surge can improve their utilization and prices, boosting profits. Capital cycle theory would say when everyone else is overinvesting, you might want to own the input providers who haven’t yet overbuilt mines or factories — they might enjoy a period of pricing power.

To illustrate how real these demands are, consider NVIDIA’s switch from fiber optics to copper for short connections. NVIDIA has signaled a move to use more copper cables within AI data centers, due to needing extremely high bandwidth between GPUs. This might seem small, but it may signal a major increase in copper usage. Multiply such effects across power distribution and wiring and the impact is large.

Other Infrastructure

- Data center REITs are effectively the “landlords of AI.” Equinix, Digital Realty, GDS, and similar companies have a global footprint.

- Grid and transformers: As power demand rises, manufacturers of high-capacity transformers benefit — e.g., Siemens, GE Grid, Hitachi Energy.

- HVAC companies for precision environments: Data centers need not just cooling but humidity control, fire suppression. Companies like Halma may benefit.

- Security firms: Physical security of data centers represents a growing need.

- Logistics and installation: Moving and installing thousands of heavy servers and cooling units helps logistics providers.

Building and operating AI facilities is a supply chain spanning mining, manufacturing, construction, and utilities. Some of these “arms dealers” of the AI boom may be attractive investments, especially if they have a moat or tight supply conditions. A utility serving an area of high data center growth could see years of stable, growing cash flows due to long-term power contracts with hyperscalers.

One could also think of beneficiaries in the energy sector beyond electricity — e.g., natural gas suppliers if gas power plants are main source for new electricity, or even backup diesel fuel suppliers for generators. These are more tangential but show how widespread the ripple effects can be.

As investors, we may want to construct a portfolio that underweights the big spenders and overweights the enablers and utilizers of AI. In doing so, we align ourselves with the idea of the “capital cycle” — avoid where capital is flooding in and favor those selling scarce inputs or crafting valuable outputs.

For insights into capital cycle theory, please enjoy my recent segment on the subject.

John Mihaljevic is the managing editor of Latticework and chairman of MOI Global, the research-driven membership organization of intelligent investors. John studied under former Yale CIO David Swensen and served as research associate to Nobel laureate James Tobin. He is the author of The Manual of Ideas and a winner of VIC’s prize for best idea. He holds a BA in Economics, summa cum laude, from Yale and is a CFA charterholder.