This article is authored by MOI Global instructor and Zurich Project participant Michael Lee, managing member of Hypotenuse Capital, based in North Hollywood, California.

What makes an investment successful?

There are many factors that can drive the price of a stock higher. Sometimes the fundamentals of the underlying business improve and earnings grow; with such cash flow growth a proportionate increase in valuation is rational. At other times the price of a stock may go up simply because the market grows more enthusiastic or positive about the company. Such shifts in sentiment can drive large swings in the price the market is willing to pay for a company even if the underlying earnings of the company do not change materially. Although it is possible to analyze historical market sentiment patterns, it is nonetheless very difficult to predict with any accuracy when and by how much sentiment will vary.

On the other hand, a company’s ability to successfully grow its earnings should be eminently analyzable and, in some cases, foreseeable.

How can we know what businesses will be successful before the fact? This is quite literally the million dollar question. Although we can’t turn back the clock and invest retroactively, we can study the past to search for clues as to what characteristics will lead to a company’s future success and prosperity. One case study that comes to mind is GEICO.

The Flame that Still Burns [1]

“GEICO, the company that set my heart afire 66 years ago (and for which the flame still burns).” —Warren Buffett, Berkshire Shareholder Letter, 2016

In his [2017] annual letter, The Oracle of Omaha reminisces about a car insurance company as if it were a hot crush from his adolescence. While it’s not unusual for Warren to wax effusively about a company he admires, his adulation for GEICO goes a step beyond, almost into the realm of romantic poetry. And there is good reason; GEICO, indeed, was like his first love. He first set eyes on the company at the tender age of 20 while studying under Ben Graham at Columbia Business School.

So immediate was his infatuation, he soon hopped on a train to Washington D.C. on a winter Saturday and presented himself, unannounced, at the front door of the company’s downtown headquarters which was closed for the weekend. Like a star-crossed Romeo, he pined away below the balcony and pounded on the locked front door until a confused custodian finally answered his calls and granted him entry to the chambers within. There he met Lorimer Davidson, who would later become GEICO’s CEO, and then the courtship began in earnest.

So hot was Warren’s passion for GEICO that, upon returning home to Omaha after graduating from Columbia, he penned a public letter of his affection, entitled “The Security I Like Best”, which he published in a leading financial periodical. Apparently, Buffett had no problem with long-distance relationships or public displays of affection. He pitched the shares to anyone who would listen and bought a substantial position for his own account over the course of 1951; according to his own records, at the end of that year he held 350 shares accumulated at a cost of $10,282.

As with so many young romances, Warren’s initial affair with GEICO was short-lived. He sold the shares in 1952 for handsome proceeds of $15,259 or a 50% gain over his cost. While the profits of this early episode with GEICO were objectively material, Warren himself acknowledges his misdeed here:

“This act of infidelity can partially be excused by the fact that Western [the interloper that seduced Buffet into dumping GEICO] was selling for slightly more than one times its current earnings, a P/E ratio that for some reason caught my eye. But in the next 20 years, the GEICO stock I sold grew in value to about $1.3 million, which taught me a lesson about the inadvisability of selling a stake in an identifiably-wonderful company.”

Warren is understandably harsh on himself for his “infidelity” in this fling as his choice cost him dearly. All was not lost in the relationship though as the two would come together again a quarter of a century later in 1976 when GEICO found itself lost in a quagmire of underwriting losses and teetering towards insolvency. Buffett’s friend, Kay Graham of the Washington Post, arranged a reunion of sorts between Buffett and newly-appointed GEICO CEO, Jack Byrne, at her Georgetown home. The tryst rekindled the flame and Buffett was once again buying shares of GEICO the very next morning. Soon Berkshire Hathaway would own over a third of GEICO’s shares.

A decade later in 1987, Buffett informed his shareholders that GEICO, amongst others, should be considered a “permanent” holding; in other words, “‘til death do we part.” Finally, in 1995, Buffett committed himself wholly to the relationship and Berkshire Hathaway bought out the remaining shares of GEICO that it did not already hold.

What was it exactly that made the Oracle of Omaha fall so hard for an insurance company? It is one thing for someone to fall for a first love at a young age but to be so adoring of a single company almost 70 years later is a truly unique kind of affection.

The Key to Success

At the core of Buffett’s adulation for GEICO is its simple ability to deliver a product to its customers at a substantially lower cost than its competitors. As Buffett explains in his shareholder letters:

“When I was first introduced to GEICO in January 1951, I was blown away by the huge cost advantage the company enjoyed compared to the expenses borne by the giants of the industry. It was clear to me that GEICO would succeed because it deserved to succeed.” [The emphasis is Buffett’s own.]

GEICO has a distinguishing feature which sets it apart from the rest of the industry: it sells directly to customers. By avoiding the cost of supporting a network of independent commission-carrying sales agents, GEICO has a considerably more efficient operation than other insurers. In fact, GEICO’s expense-to-premiums written ratio is approximately 15%, versus 25% for the average auto insurance carrier. This significant cost advantage allows GEICO to price its product at a level that almost no other competitor can profitably sustain. As Buffett explained in 1976:

“I always have been attracted to the low-cost operator in any business and, when you can find a combination of (i) an extremely large business, (ii) a more or less homogenous product, and (iii) a very large gap in operating costs between the low-cost operator and all of the other companies in the industry, you have a really attractive investment situation.”

I will note that although GEICO is an industry leader when it comes to cost, the company doesn’t just skimp on quality. According to insure.com, GEICO receives customer satisfaction ratings of 94 and 89 for claims experience and customer service, respectively. 87% of reviewers would recommend GEICO to a friend. GEICO’s product is not only low cost but also high quality.

Deviant Behavior

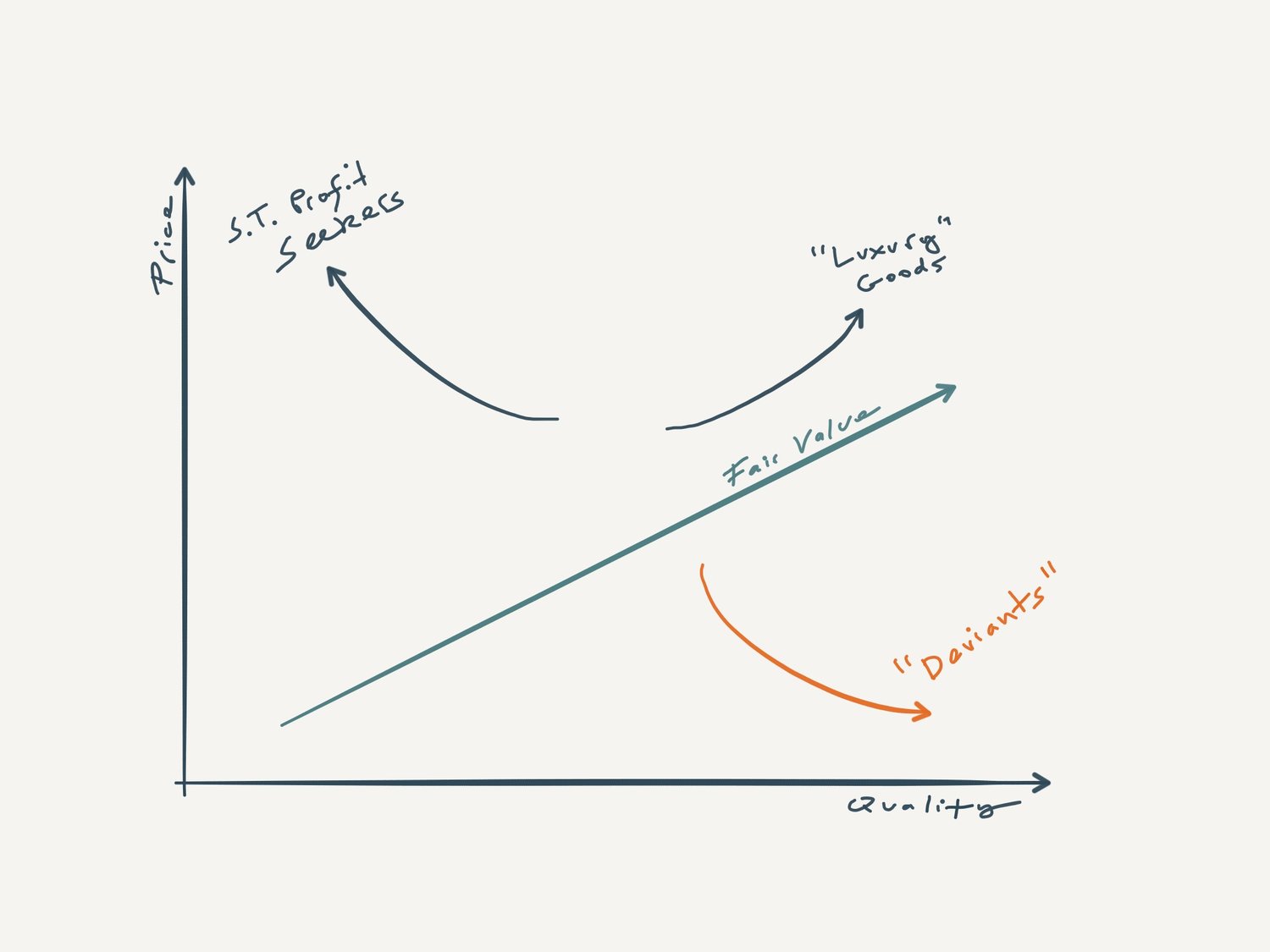

Of course, the relationship between price and quality has always been a useful framework for people looking to buy something. This is why websites like Yelp, TripAdvisor and Amazon are so popular: it’s extraordinarily useful to know the quality of a product or service prior to purchase. And generally, one expects that as a product’s quality increases, so too does its price. Thus, if one were to plot a two-dimensional chart with quality on the x-axis and price on the y-axis, one would expect that a line representing a given product’s expected price would be upwardly sloping to the right as quality increases.

Now, an inherent tension exists in that a typical business that is trying to maximize profits in the short-term is incentivized to raise prices but lower costs. Of course, it is difficult to cut costs without sacrificing quality. Hence many firms tend to migrate towards the upper left-hand quadrant of the chart (low quality, high price). This is a rational decision for any firm trying to maximize profits in the short-term but it creates challenges over the long-run since no one likes to pay a lot of money for a shoddy product.

On the other hand, there are companies that pride themselves upon crafting extraordinarily high-quality products and will charge exorbitant prices for them (think of luxury goods makers like Hermès). Economists and business school professors might argue that this is the mark of a successful firm: significant pricing power and the ability to realize above average profit margins and returns on investment.

It is entirely understandable and common for firms to move up the price dimension of our chart; conversely, firms that try to move down the price dimensions are rare, and even more unusual are the firms that do so while also moving to the right on the quality dimension. Such companies are “deviants” in a competitive world typically obsessed with expanding profit margins. Yet this is the domain where GEICO operates and it is a fundamental driver of why the company has been so successful.

This commitment to providing a high-quality product at a bargain price is an unusual ethos but one that drives a decidedly virtuous cycle. Customers who buy a high-quality product at a low price delight at their fortune of getting a good bargain. They return as repeat customers and recommend the product to their friends. As such a company grows and benefits from economies of scale; the deviant can continue to offer even lower prices and even better service, thus allowing it to capture even more market share.

This ability to march down and to the right on the cost-quality curve creates an ever-widening and durable moat which competitors cannot cross. Deviants make their money not by squeezing every last penny of margin out of any given customer and supplier, but by operating at extraordinarily low margins where the competition cannot follow. The scale benefits rewarded to deviants by happy customers make it still harder for competitors to retrace a deviant’s footsteps. Deviants may sacrifice profits on an individual unit basis but make up for it in sheer volume.

Today, GEICO is a powerhouse within the insurance industry. GEICO is the second largest auto insurer in the nation with 12% market share, which is up from 2.5% when Berkshire took control of it in 1995. GEICO is creeping up on the country’s leading auto insurer, State Farm, which has about 18% share. GEICO wrote $26 billion in premiums in 2016 up from $21 billion just two years prior.

GEICO provides a hoard of cash for Buffett to invest in the form of its $17 billion float while also operating at an underwriting profit. GEICO’s continually increasing success is undeniable and very much “deserved.”

There are other examples of deviant low-cost high-quality ethos companies who have earned dramatic success. Consider Costco, which by rule will never markup merchandise more than 14% above cost and earns less than a 1% pretax operating margin on its retail sales, even on “luxury” items like fine wines, handbags and diamonds. Today, Costco has a fanatical membership base and is one of the most successful and prosperous retailers in the world.

Think of Southwest Airlines, which started as a misfit regional air carrier serving just three cities in Texas, and became one the largest air carriers in the U.S., all based on the proposition of providing a wonderful flying experience at a lower price.

Contemplate the prosperity of fast food chain In-N-Out Burger, which for decades has provided freshly made, never frozen hamburgers at an absurdly low cost. To this day, the queues for the drive-through at In-N-Out often snake through the parking lot and spill into the street.

These companies have earned the right to succeed because the deviant ethos of low-price, high-quality is a winning one-two knockout proposition for the consumer. In short, these companies deserve to succeed and consequently have delivered remarkable returns for their owners.

Most companies try to find ways to make their stock prices go up. Many of them do so by trying to grow profits by lowering costs and raising prices. A few might be pushing the boundaries of higher quality but still expect higher prices as a reward for their efforts.

It takes a contrarian mentality to steer a business down the deviant path of lower prices while offering higher quality. Such players are forgoing profits in the near-term to win over the long-term. They don’t get fat off of excessive margins but rather reinvest in delivering superior value to their customers. They stay lean and run ever faster on behalf of their clients. These are a unique and rarely seen breed.

Not every successful company will be a deviant, nor will every investment we make fall under this criteria; yet when deviants do present themselves, they can prove to be astoundingly successful businesses and, by extension, wonderful investments.

An Oracle and his Gecko

A parting observation about GEICO’s deserved success revolves around its reptilian spokesperson, who has also earned Warren Buffett’s affection and admiration. Buffett wrote in his 2014 shareholder letter:

“Our gecko never tires of telling Americans how GEICO can save them important money. The gecko, I should add, has one particularly endearing quality – he works without pay. Unlike a human spokesperson, he never gets a swelled head from his fame nor does he have an agent to constantly remind us how valuable he is. I love the little guy.”

The witty lizard certainly does seem like the ideal employee. However, given that he is a computer rendering, perhaps it’s not really that remarkable. What is remarkable is the resemblance the gecko bears to another important Berkshire Hathaway employee: the Chairman himself. Consider that Buffett has worked for over five decades at a nominal salary ($100k annually) with no bonus, and no equity grants or stock options. He’s never complained about the size of his paycheck and certainly has never called on an agent to negotiate his contract.

Despite his fortune and fame, Buffett keeps a low profile and his ego in check (how many billionaires still drive themselves through the McDonald’s drive-through on the way to work every morning?). Buffett’s adoration of the gecko is well-placed but Buffett himself certainly did more than his fair share to position Berkshire itself to succeed.

[1] Much of the factual information regarding Buffett’s history with GEICO comes from David A. Rolfe of Wedgewood Partners who wrote a wonderfully in-depth paper on the subject. While I am indebted to him for the original source documents and analyses he provided, he deserves no blame for gratuitous stylistic embellishments in this discussion; that burden is mine alone to shoulder.

Disclaimer: THIS WEBSITE AND ITS CONTENTS SHALL NOT CONSTITUTE AN OFFER TO SELL OR THE SOLICITATION OF ANY OFFER TO BUY WHICH MAY ONLY BE MADE AT THE TIME A QUALIFIED OFFEREE RECEIVES A CONFIDENTIAL PRIVATE OFFERING MEMORANDUM, WHICH CONTAINS IMPORTANT INFORMATION (INCLUDING INVESTMENT OBJECTIVE, POLICIES, RISK FACTORS, FEES, TAX IMPLICATIONS AND RELEVANT QUALIFICATIONS), AND ONLY IN THOSE JURISDICTIONS WHERE PERMITTED BY LAW.

About The Author: Michael Lee

Mike founded Hypotenuse Capital Management in 2013. Previously, he was a partner at Royal Capital Management, a multi-billion dollar investment manager in New York. Prior to Royal, Mike was a private equity associate at Parthenon in Boston and an investment banking analyst at Bear Stearns in New York.

More posts by Michael Lee