This article by Phil Ordway has been excerpted from a letter of Anabatic Investment Partners. In it, Phil discusses the rationale behind Anabatic’s recent investment in the equity of three U.S.-based airlines.

The premise of our investment is simple: The next few quarters are uncertain at best, but I believe that industry demand and earnings will be far higher over the next several years. The question, then, is whether certain individual businesses have the resilience to reap the benefits of that growth, and whether the offered price gives us an attractive return with room to be wrong. In both cases I believe the answer is yes.

Most domestic airline equities suffered sharp price declines this summer due to a confluence of factors, and I believe this creates an attractive opportunity over a multi-year horizon. As always, the test remains our willingness to own these securities – partial ownership stakes in businesses – for the next five or 10 years. On that basis, I’m comfortable having a material portion of our capital invested in these companies.

Before going further a brief comment on the industry is required. (There is more background information in the Appendix.) The domestic airline industry has undergone a dramatic restructuring in the past 5-10 years and I think it will support a bright future. I’d had an interest in the sector for years, but a combination of inertia and an ingrained bias against airline investments had kept me from doing any meaningful research. When I finally did, beginning in the summer of 2016, a few features stood out:

Industry structure and financial strength. Competition remains tough in many individual markets, but consolidation has changed the overall pricing dynamic and created a level of profitability and stability that is unprecedented in the industry. Current operating margins are generally in the 10-20% range – a level that generates ample free cash flow – and I estimate that most airlines will generate significant profits even in a downturn. Balance sheets and cost structures are also far healthier and they will be able to withstand future cyclical downturns and exogenous shocks.

Fares and fees. It is far cheaper to fly in the U.S. today than it was a few decades ago but pricing is also far more rational. This is still a high-fixed and low-variable cost business, but consolidation has enabled the airlines to compete without destroying each other in the process. As a partial offset to lower inflation-adjusted fares and the recent capital spending, the airlines now generate material revenues and high-margin profits from non-ticket fees and loyalty/mileage programs tied to credit cards. Cyclicality has not been eliminated but it has been muted to a large degree.

Ultra-low-cost carriers (ULCCs). Customers want low prices, and that simple fact dictates the entire business model. An airline taking a passenger from point to point is offering something close to a commodity, and price is by far the most important factor in the purchase decision. There is some customer loyalty for certain companies, and mileage programs can help, but these are not true brands that affect behavior on a large scale.[1] A customer with his own money is likely to pick an airline that will save him $50, and the business with the lowest cost will often win in these circumstances. Low costs that are “reinvested” in lower prices can also create an enormous advantage over time. Airlines like Southwest and Ryanair are good examples of these concepts, and when I pulled my head out of the sand to look at what made them two of the world’s most successful businesses what I saw would be familiar to any analyst looking at Costco, Amazon, Nucor, or IKEA. A cost advantage is hard to establish and easy to lose, but if maintained it makes life miserable for the competition. In the U.S. market the ULCCs have a material and growing cost advantage that will enable years of future growth at attractive margins and returns on capital.

The history of the industry is littered with bankruptcies and failures, and it always pays to focus on the potential for loss – more on that below. Right now I see far more pessimism than optimism in the market, and that bodes well for bargain-hunting investors. There have even been some prominent articles in the media positing “the death of the ULCC model” or “a return to the bad old days of the airline industry.” In my opinion, the facts point to just the opposite.

The most prominent fear today seems to be centered on price competition. After a multi-year ULCC boom that peaked in 2014, unit revenues had been falling for two years before picking up in early 2017. In June, however, United kicked off a new round of price matching at its hubs, and the competition has since spread across the industry. The network carriers believe that their most valuable assets are their hubs and they are defending their home turf to prevent an upstart low-cost competitor like Spirit or Frontier from taking too much volume.[2]

The network carriers are not, however, picking a fight – they’re matching Spirit and Frontier’s fares, not undercutting them. Network carriers do have low marginal costs on flights at their hubs (thanks to the flow of connecting traffic), but it is the ULCCs with the long-term advantage in direct, point-to-point competition.[3] The network carriers are also taking a loss on a substantial portion of the seats they sell at the ULCC-level prices via their new “Basic Economy” fares.

Ironically, Basic Economy is a good thing for the industry and the customer. “Unbundling” fares so that customers pay only for the services they want is rational and keeps total fares down.[4] Basic Economy also delineates and limits the amount of capacity dedicated to ULCC competition, checking their growth without destroying anyone’s margins; it validates and spreads the low-fare-plus-ancillary-fees model; and it gives the networks another tool for price segmentation. With growing demand, this does not have to be a zero-sum game.

When a recession or some exogenous calamity strikes the industry, I believe the recovery will be swift. United – and Southwest, to a lesser degree – just suffered a major disruption from Hurricane Harvey.[5] Despite thousands of cancelled flights and an immediate spike in jet fuel of 20-40%, United still projects solid profitability this quarter. Over a more meaningful period, Southwest hasn’t posted a full-year GAAP net loss in 44 years and counting. It has been profitable and growing across numerous recessions and shocks, and it grew almost uninterrupted through the 2007-09 financial crisis. Now the rest of the industry looks more like Southwest – and vice versa – than ever before.

Spirit has also been profitable each year since its conversion to a ULCC strategy took hold in 2007, and it remained profitable through the financial crisis as well. From a starting level of $763 million in 2007, Spirit’s sales never dipped below $700 million in any full year. Sales had doubled by 2013 and they have nearly doubled again since 2013.

A lower growth rate would not be a surprise over the next five years, although the ULCCs should grow a few points ahead of the industry pace and it is hard to imagine a world in which demand does not grow over multi-year periods. With any demand growth, a low/mid-teens operating margin and incremental returns on capital above 20% should enable strong investment returns.

So why is there so much pessimism right now? I think part of the explanation lies in a deep skepticism of the industry. That skepticism was well deserved for several decades, and it initially deterred me from even looking at the industry. Despite undeniable improvements it’s as if investors are just waiting for the other shoe to drop. Old ideas can be hard to break.

The other part of the explanation, which may be even more important, stems from a myopic focus on the immediate future. As Joel Tillinghast recently wrote in his book Big Money Thinks Small, investors often skip the hard, important question (“What’s it worth?”) and instead answer an easier question (“What comes next?”). Increasing price competition, higher fuel costs, war on the Korean peninsula, a recession, a terrorist attack, a catastrophic hurricane (or even two catastrophic hurricanes) – there are plenty of reasons to worry about “what comes next.”[6] None of these developments are welcome, of course, but their short-term impact can swing the pendulum too far in the direction of pessimism. The fear of further price declines can also create its own feedback loop, and fear alone may be responsible for keeping market prices at bargain levels.

At current prices, investors are getting an approximate earnings yield of 8-12%. The worry, of course, is that recent industry conditions were a mirage in the desert, setting the stage for future earnings will be far lower. That is a valid concern – it is a cardinal sin to buy a low-quality company at what looks like a cheap price due to earnings that are temporarily inflated. As noted above, though, I think the opposite is true: these are better-than-average companies heading into a period of growth. I don’t discount the potential for volatile earnings – the path is certain to be bumpy – but in my opinion this industry is just now entering a period of prosperity.

Another piece of good news that might be overlooked is that the U.S. airlines can now reinvest profitably in their businesses. For decades they were forced to spend mountains of capital on investments that were unlikely to offer any meaningful return. Today, most capital expenditures come with returns above 15%, and as such most airlines have been spending heavily in recent years to upgrade their fleets.[7] Spirit and Frontier have two of the youngest fleets in the industry, and American and Alaska each have younger fleets than their direct peers. With the newer technology also comes better fuel efficiency, a savings that can be 10% or more compared to older aircraft.

The ULCCs have an especially strong incentive to reinvest their earnings. As a small share of the overall market, they have room to grow before they begin to compete head-to-head. Along the way they can stimulate additional demand, as low fares encourage more people to travel or to switch from other modes of transportation.[8] As demand fills up the plane the carrier’s margins and cash flow expand, funding reinvestment opportunities. Spirit and Frontier combined have about 6% of the capacity in the U.S., and I believe that share will grow over time in addition to the growth in demand for air travel across the industry.

Capital allocation is a point of strength as well. After decades of fighting a losing war with their balance sheets, airline executives can now have thoughtful deliberations about the best use of their capital. Airlines are still capital intensive, but the free cash flow pouring out of the business and the credit card programs allows large investments in equipment with plenty of cash leftover for debt repayment, dividends, repurchase, joint ventures, and other strategic investments.[9] Significant debt reduction funded out of operating cash flow in recent years has left many airlines with moderate debt levels and plenty of interest coverage it the case of a downturn.[10]

None of the analysis presented above is new or notable. Most analysts (not all, but most) would agree about the core concepts of demand growth and a low-cost advantage. Many would even agree about the favorable investment prospects over a period of several years. Far fewer seem willing to wait and ride out the inevitable volatility to earn that return.

What we offer is patience. The industry remains unpredictable, and I have no reliable way to forecast exactly what the rest of this year or next year will bring. Oil prices, macro conditions, and geo-political events make these companies almost impossible to model with many analysts’ preferred degree of (false) precision. But a forecast of financial metrics down to two decimal places isn’t necessary so long as I’m right about the future success of the business model, the overall industry conditions, and the price we’re paying today.

A strong collection of like-minded partners gives us a significant advantage. With that in mind, current partners are often the best source of new partners, and we welcome your referrals.

APPENDIX

If you pardon the flood of acronyms and jargon, this table conveys most of what is important about the industry. The majority of industry capacity is controlled by the three network carriers – each with a unit cost excluding fuel of ~10-11 cents – and Southwest, which used to have a major cost advantage but is now closer to the network carriers than the ULCC segment in terms of cost.

Load factors used to swing in a much wider range, and at the low end the operating losses were substantial. Breakeven load factors vary by airline, of course, given the differing price and cost structures, but in general breakeven load factors have improved as the industry has evolved. For most airlines the breakeven load factor is in the 70s, and with a load factor in the 80s the profits are substantial. (Ryanair, as an exemplar, has recently had load factors near 97%.)

Source: company filings with the SEC and Anabatic analysis. Market data using closing prices on September 5, 2017. * Sum in bold, average in bold italic as appropriate 1 Share of total domestic revenue passenger miles for the year ended December 31, 2016. 2 Available seat miles (in millions). One seat available to be flown on a flight for one mile is one ASM. 3 Passenger revenue per available seat mile, or unit revenue — the ticket revenue and non-ticket revenue (including all fees and charges) per available seat mile. 4 Cost per available seat mile, or unit cost — the cost to fly one seat one mile. 5 Unit cost excluding fuel. 6 Unit cost excluding fuel, adjusted under varying definitions to exclude unusual/one-time impacts and gains (losses) on asset disposals, fuel hedges, etc. 7 Utilization, calculated as revenue passenger miles divided by available seat miles.

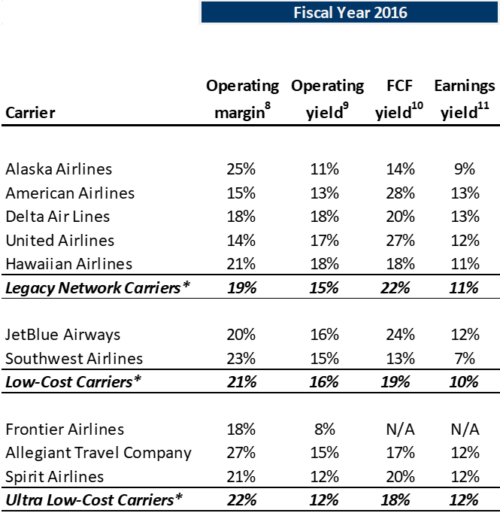

This snapshot of financial metrics and valuation based on 2016 results is instructive, with the usual caveat that past is not prologue.

Source: company filings with the SEC and Anabatic analysis. Market data using closing prices on September 5, 2017. * Sum in bold, average in bold italic as appropriate 8 Operating income divided by revenues. 9 Operating income divided by enterprise value (current market capitalization plus preferred equity plus debt plus operating leases capitalized at 7x). 10 Free cash flow (adjusted to reflect the cash flow available for allocation: generally, net income plus D&A less our estimate of required capital spending) divided by current market capitalization. 11 Net income divided by current market capitalization. 12 Operating profit less estimated income taxes divided by invested capital (debt plus common and preferred equity plus capitalized operating leases). 13 Net income divided by book equity.

Ultra-low-cost carriers

Southwest is a great business success story, and its strategy drove much of the post-regulation industry in America and the rest of the world. Ryanair copied most of the Southwest playbook and executed it to perfection in Europe, where it is now the largest European airline by passenger traffic. (Beyond some of the obvious differences among European and American travel options, Ryanair has the advantage of competing against legacy carriers that have been far less successful than the major American carriers.)

The ULCC model has its critics, but the results are undeniable. A recent survey ranked 75 airlines around the world based on operating margin.[11] Three of the top four – Allegiant, Ryanair, and Spirit – were ULCCs. (The other was Alaska, which came in third.) ULCCs fill a large, underserved segment of the market, they bring lower fares to all airline customers, and they make a lot of money in the process.

The linchpin to the ULCC model in the U.S. has been Bill Franke. A former attorney with a variety of business experiences, Mr. Franke helped pull America West out of bankruptcy in the 1990s. Ever the astute business student, Franke was a pre-IPO investor in Ryanair and a longstanding competitor against Southwest. Both experiences taught him the power of lost costs, and he took that lesson to heart. After he hired an executive team at America West that today runs must of the industry, he retired on September 1st, 2001. In the aftermath of the 9/11 tragedy he founded his own private equity firm, Indigo Partners, to invest in airlines. The results have been spectacular, and the companies he has founded or managed (Tigerair in Singapore, Wizz Air in Hungary, Spirit and Frontier in the U.S.) have reshaped the industry.

Indigo Partners is now the sole owner of Frontier. In the 2nd quarter of 2017 Frontier filed for a long-awaited IPO, but Frontier decided to postpone the offering as the price competition (primarily from United) heated up during June. The timing is uncertain but I think it is likely that Frontier will eventually go public, with Indigo selling a small portion of its shares in the offering.

The obvious next step would be a merger with Spirit. Mr. Franke was the major shareholder and chairman of Spirit from 2006-2013, and he oversaw the creation of its current business model. In 2013 he sold his stake and resigned from Spirit to buy Frontier. In less than four years under Indigo Partners’ ownership Frontier has completed a successful transformation to the ULCC model. Mr. Franke has spoken openly about the desirability of ULCC consolidation, and the benefits of added scale are obvious. The urgency is low, however, as both airlines are doing well and competing head-to-head on fewer than 20% of their routes, by my estimate. Spirit also has to complete a new deal with its pilots and avoid any material shifts in its strategy or fleet composition if a Frontier merger is going to happen. I believe the logic is inescapable, but Mr. Franke is a patient manager and investor and it may be several years before a merger is consummated.

Culture

The most common complaint – from customers and investors alike – often pertains to the customer experience. For the ULCCs, those complaints often miss the point. If a traveler can afford a first- or business-class ticket, there is no comparison to a ULCC flight. For everyone else, the differences are subtle to the point of being almost arbitrary. Basic Economy is further narrowing the gap between the experience of flying the network carriers and the low-cost carriers. If a carrier can deliver a reliable service between destinations, there is no evidence that customers want to pay enough to justify in the investment in frills and amenities. People love to complain about airline service, but they also vote with their wallets several hundred million times per year and the results are clear – what they want are low fares with reliable service.

Outside of the debate about service quality, much of what makes the experience of air travel experience so frustrating is shared at the airport by all passengers. In my opinion, a significant part of what passengers hate about flying is out of the airlines’ control. TSA lines, decrepit terminals, air traffic control delays, and slow ground transportation are often a source of frustration that ruins the experience of flying even if the flight itself is acceptable.

That said, airlines do control many aspects of the flying experience and most of them leave a lot to be desired. Simple customer service problems often metastasize in a Petri dish of stress and weak culture. Small issues can spiral out of control and cause the airlines to shoot themselves in the foot, as we’ve seen several times in recent months.

Southwest had (and mostly still has) a unique, friendly culture that engendered both employee and customer loyalty. That culture has been an invaluable advantage over almost five decades. Alaska also has a unique and positive culture that it uses to its advantage.[12] Most other U.S. airlines, however, have a culture that would rank somewhere between average and poor. If Spirit or another ULCC could replicate a Southwest- or Ryanair-esque culture it would be huge advantage. I do think progress is being made, but changing a company’s culture might be the only thing harder than changing a company’s cost structure. In either case, eventual success will take years if it comes at all.

Co-branded credit cards and loyalty programs

Most people are familiar with airline-branded credit cards, but as the airlines’ agreements with the card-issuing banks have been recut in recent years it has become a profit center for the airlines that may still be underappreciated. Each of the individual programs is worth many billions of dollars to American, Delta, United, Southwest and Alaska. (The other U.S. carriers have far smaller programs that are not as valuable.)

Just as the competition for high-value cardmembers at Costco caused a price war between American Express and Citi, the recent contract negotiations with many of the major airlines yielded large price increases. Airlines hide behind exclusive contracts with the banks and the premise of “trade secrets” to avoid disclosing detailed numbers. Approximations can be made, however, and airline executives are on the record confirming that it is a significant and high-margin part of the business. Based on my estimates, it is reasonable to believe that the airlines get 1.5 cents or more per “mile” on the billions of miles sold to the banks each year.[13] That cash flow also benefits working capital, as the cash comes in as soon as the miles are sold but the revenue is deferred until passengers redeem the travel or other awards. Along the way, of course, some miles are never redeemed (what’s known as “breakage,”) at a rate that may approach 10-30%, and some miles are redeemed for non-airfare awards on favorable terms to the airlines. As such, the margins for the miles sold by the airline are far higher than in the rest of the business. It is reasonable to assume that the profit margin on this business is in the 30-50% range, if not higher.[14]

Alaska may be smaller than the Big Four of American, Delta, United and Southwest, but it may have the best loyalty program in the industry. It has made enrollment growth on its card deal with Bank of America a major priority in its Virgin American integration and its overall growth plan, even tying a small portion of employees’ incentive pay to the program. The numbers are significant – Alaska disclosed $900 million of 2016 cash flow from its loyalty programs – and I believe they will only increase over time due to organic growth and the Virgin America acquisition. American, as another example, could see an incremental cash flow benefit of $500 million to $1 billion per year starting in 2018, and given that it is due to a price hike the incremental profit margins could be close to 100%. Delta expects the $2.7 billion of 2016 revenue it generated from its American Express partnership to hit $4 billion by 2021, and the incremental $300 million per year should yield very high margins.[15]

Airlines also benefit from generating revenues that are not directly tied to the airline business. In an industry downturn or recession the use of credit cards and the resulting cash flow from the mileage programs may decline, but it likely to decline far less than the airline business itself. That cash flow will provide a material cushion over time.

Airlines’ Bankers (co-branded airline credit cards are lucrative — and growing more so — for both big banks and the carriers)

Source: Bloomberg.

[1] Alaska may have one of the best airline brands in the country, if not the world. Its loyal fliers often choose Alaska if the price is close, and the company rewards its customers with award-winning customer service. Alaska serves very attractive markets on the West Coast and it recently acquired Virgin America to expand further in California and on the East Coast. The integration is ongoing, but if Alaska can retain its cost advantage over the network carriers, maintain its culture, and capture the attractive growth in its markets, the future is bright.

[2] Scott Kirby, president of United, was responsible for the first implementation of this strategy in 2015 when he was in a similar role at American. That price competition did make a dent in unit revenues, but all of the U.S. airlines still posted exceptional profits in 2015 and 2016. A large part of the boost in profits was the drop in oil, but even if fuel jumps 25-50% (as it just did after Hurricane Harvey) I estimate pre-tax profit margins would still be in the 5-15% range, depending on the company. A rise in fuel costs would also be somewhat of a benefit to Spirit, as it would widen the gap between its cost and fares and those of its competitors.

[3] Operating a hub is an expensive proposition and one that the ULCCs largely avoid. ULCCs also do not have to incur countless other costs that are required at a full-service airline. Labor and fuel are the two biggest expenses for any airline, and ULCCs maximize their efficiency on both fronts. Another significant cost advantage stems from the ULCCs’ labor force – as younger/newer airlines that are growing more rapidly than their peers, the ULCCs can attract younger pilots at lower pay with the offsetting benefit of more rapid career progression and more flexible work schedules. With labor representing a quarter to a third of operating expenses, the savings are significant.

[4] Spirit now gets more than 40% of its passenger revenue from fees and charges. The total revenue has declined from about $130 per flight per passenger in 2012-2014 to $107 in 2016, but the average non-ticket revenue has been close to flat. And yes, the ULCCs’ all-in fares – with all fees included – is still lower than the average fares on other carriers.

[5] United Airlines’ CFO Andrew Levy recently said that Hurricane Harvey created “the largest operational impact in the company’s history.” (http://wsw.com/webcast/cowen43/ual/) The company has grown and changed since prior disruptions, and Mr. Levy wasn’t trying compare horrific human tragedies. But from a business-only perspective it is worth noting that the result is not financial distress but lower quarterly earnings guidance and a pre-tax margin that is still estimated to be 8-10%.

[6] Spirit has the added complication of a pilot contract negotiation that is in arbitration. During the 2nd quarter the negotiation resulted in some minor but material work disruptions by some pilots, and further labor problems would be a major concern. Most of the other carriers have agreed to new labor contracts in recent years, and in almost all cases the unit costs will be rising. The relative differences, of course, are all important, and Spirit should retain a large advantage even if the contract, as expected, results in an incremental $1 billion of pilot wages over the life of the deal.

[7] By my calculation, all of the major U.S. carriers are earning a return on invested capital (after-tax net operating profit over the sum of debt, equity and capitalized leases) of 10-25%. Leverage varies, but that results in a return on equity of approximately 15-40%.

[8] Spirit estimates an average 35-40% year-over-year increase in passenger traffic on routes it entered between 2007-2016. (Source: https://goo.gl/j6XbSa)

[9] Buybacks are often misused, but in the case of the major U.S. airlines the recent past has been encouraging: American, Delta, United, Southwest, and Alaska have reduced their share counts by 35%, 16%, 24%, 21%, and 14%, respectively in the past 3-5 years. Those repurchases were all made at attractive prices and not done to the detriment of the balance sheet (most companies reduced debt at the same time). It is also encouraging that most airlines have made massive investments in their fleets using operating cash flow. (Source: company filings with the SEC)

[10] Pension obligations are a material liability at some airlines, although most of the plans are well funded and can be supported by operating cash flow in the normal course of business. Operating leases must also be capitalized in any consideration of overall financial leverage.

[11] Source: Airline Weekly

[12] For anyone who hasn’t experienced Alaska firsthand, this article (“Why Little Alaska Airlines Has the Happiest Customers in the Skies”) explains the culture pretty well. https://goo.gl/RfTD7V

[13] Note that a “mile,” as used in the context of a loyalty or frequent flyer program, does not compare to an actual mile in the context of the business. An average one-way flight (a “stage length”) is just over 1,000 miles, and an average coach fare on that trip might be $80-$120 on a ULCC, $140-$175 on LUV/ALK/JBLU, and $180-$200 on UAL/AAL/DAL. That same trip would likely require 10,000 – 15,000 “miles” or points. So if each of those “miles” was sold to the issuing banks at $0.015-$0.020, that would bring revenue equal to or exceeding most of the cash fares, with all of the breakage falling straight to the bottom line.

[14] United disclosed ~41% net margins in its loyalty program segment in 2005 documents related to its bankruptcy proceeding. (Source: SEC and bankruptcy court filings — https://goo.gl/KtDFgn and https://goo.gl/NMDYSP). Those disclosures ended in 2006 but prices have generally moved in favor of the airlines since that time. The business has also grown: in 2005 it was 5% of operating revenues, and that number is closer to 12% today. (Source: https://goo.gl/i9Dty4)

[15] Source: company filings with the SEC (https://goo.gl/t7m3c9)

IMPORTANT NOTE

Gross Long and Gross Short performance attribution for the month and year-to-date periods is based on internal calculations of gross trading profits and losses (net of trading costs), excluding management fees/incentive allocation, borrowing costs or other fund expenses. Net Return for the month is based on the determination of the fund’s third-party administrator of month-end net asset value for the referenced time period, and is net of all such management fees/incentive allocation, borrowing costs and other fund expenses. Net Return presented above for periods longer than one month represents the geometric average of the monthly net returns during the applicable period, including the Net Return for the month referenced herein. An investor’s individual Net Return for the referenced time period(s) may differ based upon, among other things, date of investment. In the event of any discrepancy between the Net Return contained herein and the information on an investor’s monthly account statement, the information contained in such monthly account statement shall govern. All such calculations are unaudited and subject to further review and change.

For purposes of the foregoing, the calculation of Exposure Value includes: (i) for equities, market value, and (ii) for equity options, delta-adjusted notional value.

THE INFORMATION PROVIDED HEREIN IS CONFIDENTIAL AND PROPRIETARY AND IS, AND WILL REMAIN AT ALL TIMES, THE PROPERTY OF ANABATIC INVESTMENT PARTNERS LLC, AS INVESTMENT MANAGER, AND/OR ITS AFFILIATES. THE INFORMATION IS BEING PROVIDED SOLELY TO THE RECIPIENT IN ITS CAPACITY AS AN INVESTOR IN THE FUNDS OR PRODUCTS REFERENCED HEREIN AND FOR INFORMATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY.

THE INFORMATION HEREIN IS NOT INTENDED TO BE A COMPLETE PERFORMANCE PRESENTATION OR ANALYSIS AND IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE. NONE OF ANABATIC INVESTMENT PARTNERS LLC, AS INVESTMENT MANAGER, THE FUNDS OR PRODUCTS REFERRED TO HEREIN OR ANY AFFILIATE, MANAGER, MEMBER, OFFICER, EMPLOYEE OR AGENT OR REPRESENTATIVE THEREOF MAKES ANY REPRESENTATION OR WARRANTY WITH RESPECT TO THE INFORMATION PROVIDED HEREIN. AN INVESTMENT IN ANY FUND OR PRODUCT REFERRED TO HEREIN IS SPECULATIVE AND INVOLVES A HIGH DEGREE OF RISK. THERE CAN BE NO ASSURANCE THAT THE INVESTMENT OBJECTIVE OF ANY SUCH FUND OR PRODUCT WILL BE ACHIEVED. MOREOVER, PAST PERFORMANCE SHOULD NOT BE CONSTRUED AS A GUARANTEE OR AN INDICATOR OF THE FUTURE PERFORMANCE OF ANY FUND OR PRODUCT. AN INVESTMENT IN ANY FUND OR PRODUCT REFERRED TO HEREIN CAN LOSE VALUE. INVESTORS SHOULD CONSULT THEIR OWN PROFESSIONAL ADVISORS AS TO LEGAL, TAX AND OTHER MATTERS RELATING TO AN INVESTMENT IN ANY FUND OR PRODUCT.

THIS IS NOT AN OFFER TO SELL OR SOLICITATION OF AN OFFER TO BUY AN INTEREST IN A FUND OR PRODUCT. ANY SUCH OFFER OR SOLICITATION WILL BE MADE ONLY BY MEANS OF DELIVERY OF A FINAL OFFERING MEMORANDUM, PROSPECTUS OR CIRCULAR RELATING TO SUCH FUND AND ONLY TO QUALIFIED INVESTORS IN THOSE JURISDICTIONS WHERE PERMITTED BY LAW.

ALL FUND OR PRODUCT PERFORMANCE, ATTRIBUTION AND EXPOSURE DATA, STATISTICS, METRICS OR RELATED INFORMATION REFERENCED HEREIN IS ESTIMATED AND APPROXIMATED. SUCH INFORMATION IS LIMITED AND UNAUDITED AND, ACCORDINGLY, DOES NOT PURPORT, NOR IS IT INTENDED, TO BE INDICATIVE OR A PREDICTOR OF ANY SUCH MEASURES IN ANY FUTURE PERIOD AND/OR UNDER DIFFERENT MARKET CONDITIONS. AS A RESULT, THE COMPOSITION, SIZE OF, AND RISKS INHERENT IN AN INVESTMENT IN A FUND OR PRODUCT REFERRED TO HEREIN MAY DIFFER SUBSTANTIALLY FROM THE INFORMATION SET FORTH, OR IMPLIED, HEREIN.

PERFORMANCE DATA IS PRESENTED NET OF APPLICABLE MANAGEMENT FEES AND INCENTIVE FEES/ALLOCATION AND EXPENSES, EXCEPT FOR ATTRIBUTION DATA, TO THE EXTENT REFERENCED HEREIN, OR AS MAY BE OTHERWISE NOTED HEREIN. NET RETURNS, WHERE PRESENTED HEREIN, ASSUME AN INVESTMENT IN THE APPLICABLE FUND OR PRODUCT FOR THE ENTIRE PERIOD REFERENCED. AN INVESTOR’S INDIVIDUAL PERFORMANCE WILL DIFFER BASED UPON, AMONG OTHER THINGS, THE FUND OR PRODUCT IN WHICH SUCH INVESTMENT IS MADE, THE INVESTOR’S “NEW ISSUE” ELIGIBILITY (IF APPLICABLE), AND DATE OF INVESTMENT. IN THE EVENT OF ANY DISCREPANCY BETWEEN THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN AND THE INFORMATION IN AN INVESTOR’S MONTHLY ACCOUNT STATEMENT IN RESPECT OF THE INVESTOR’S INVESTMENT IN A FUND OR PRODUCT REFERRED TO HEREIN, THE INFORMATION CONTAINED IN THE INVESTOR’S MONTHLY ACCOUNT STATEMENT SHALL GOVERN.

NOTE ON INDEX PERFORMANCE

INDEX PERFORMANCE DATA AND RELATED METRICS, TO THE EXTENT REFERENCED HEREIN, ARE PROVIDED FOR COMPARISON PURPOSES ONLY AND ARE BASED ON (OR DERIVED FROM) DATA PUBLISHED OR PROVIDED BY EXTERNAL SOURCES. THE INDICES, THEIR COMPOSITION AND RELATED DATA GENERALLY ARE OWNED BY AND ARE PROPRIETARY TO THE COMPILER OR PUBLISHER THEREOF. THE SOURCE OF AND AVAILABLE ADDITIONAL INFORMATION REGARDING ANY SUCH INDEX DATA IS AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST.

About The Author: Philip Ordway

Philip Ordway is Principal and Portfolio Manager of Anabatic Fund, L.P. Previously, Philip was a partner at Chicago Fundamental Investment Partners (CFIP). At CFIP, which he joined in 2007, Philip was responsible for investments across the capital structure in various industries. Prior to joining Chicago Fundamental Investment Partners, Philip was an analyst in structured corporate finance with Citigroup Global Markets, Inc. from 2002 to 2005, where he was part of a team responsible for identifying financing solutions for companies initially in the global power and utilities group and ultimately in the global autos and industrials group. Philip earned his M.B.A. from the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University in 2007 and his B.S. in Education & Social Policy and Economics from Northwestern University in 2002.

More posts by Philip Ordway